ROBERT GLENISTER INTERVIEW: ‘MANY MEN OF A CERTAIN AGE FEEL LET DOWN BY THE SYSTEM’

In the past few years, whenever a psychological thriller or a crime drama was shown on TV, Robert Glenister has found himself having a minor crisis. “I’d think: ‘Why am I not in this show? What’s the problem?’ And then I realise that everyone on screen is 45 or younger. And I go: ‘Oh of course! I’m 64!’.”

The easygoing star of two of the BBC’s best crime shows in recent years, Hustle and Spooks, gives a wry chuckle. “As you get older you notice a change in the parts you are asked to play,” he adds. “It’s something women come up against a lot in this industry, of course, but so do men. Television execs are always chasing the 18-30 demographic.”

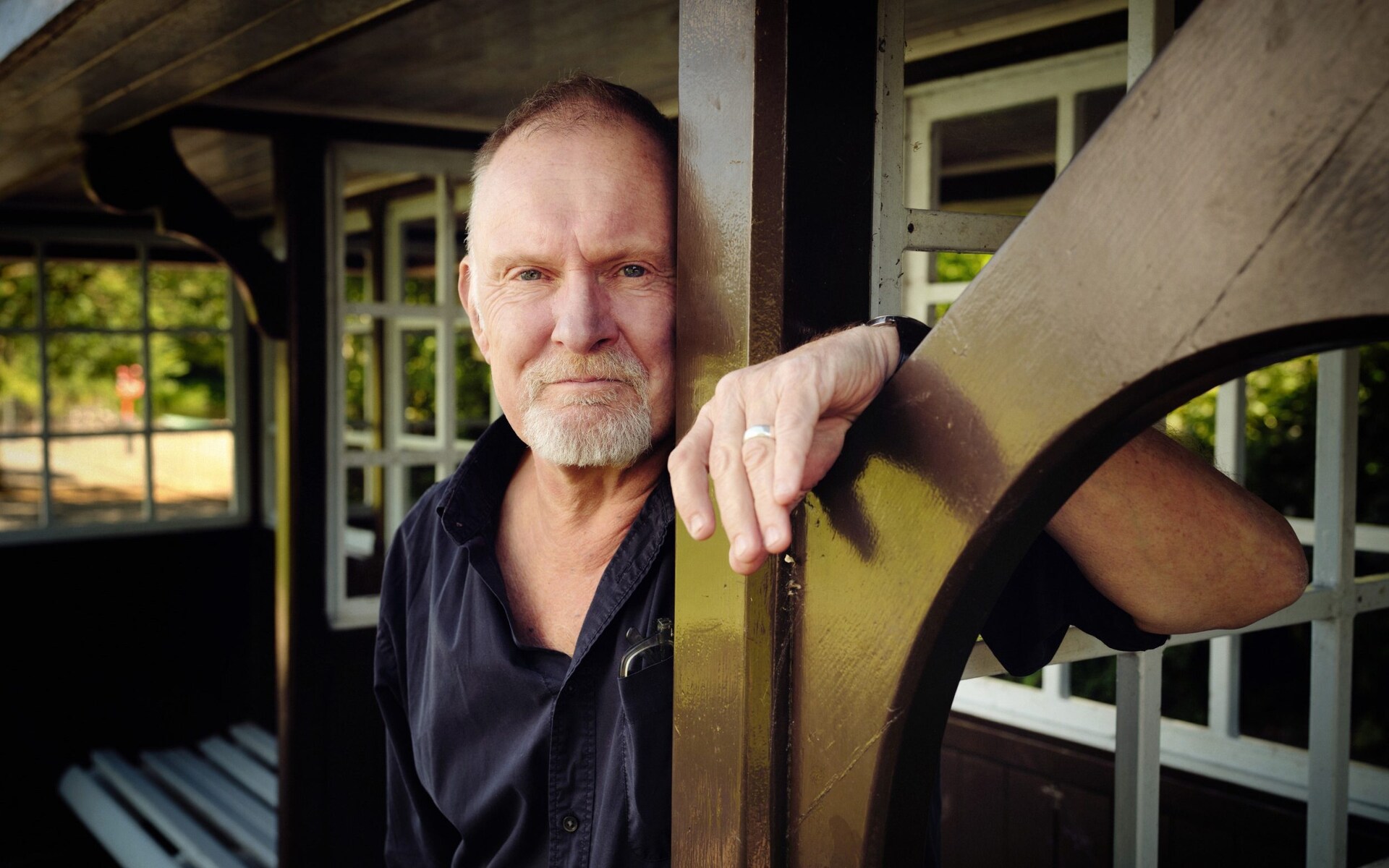

Sitting outside on a sunny day at a cafe in Dulwich, south-east London, near where he lives, Glenister is instantly recognisable as the chameleon fixer Ash “Three Socks” Morgan from the much-loved conman drama Hustle – a role he played with visible relish for all eight seasons between 2004-2012. Yet while modern TV executives may indeed be obsessed with casting on the basis of an actor’s Instagram following, Glenister remains an in-demand character actor.

In his latest show, The Night Caller, a taut, apprehensive slowburn thriller, he plays a lonely, recently divorced taxi driver, Tony, who, while gliding through the feral decadence of after-hours Liverpool, develops a deluded, intimate obsession with Lawrence, a DJ (a deliciously slippery Sean Pertwee) who fronts a late-night radio call-in. It would be a spoiler to reveal much more, but Tony, a former teacher forced to leave the profession following an incident with a pupil, perceives in Lawrence’s soothing tones a sympathetic and increasingly dangerous endorsement for his feelings of ill-treatment and alienation.

“The show feels very prescient to me,” says Glenister. “Lawrence certainly taps into the feeling people have of being ignored, this fear we have that cities have become lawless and unprotected. I think people are far more on edge now. I never see a police officer on the beat round here. It feels as though there is a much lower risk of criminals being caught, and people are scared.”

As a boy, growing up in Harrow Weald on the edges of London, Glenister briefly wanted to be a policeman himself. “I grew up with The Sweeney, so I had a very glamorous image of what it would be like,” he says. “I certainly had no moral notion about wanting to do good.” Instead, he made his name playing cops in shows such as Juliet Bravo and A Touch of Frost and, most recently, as the disaffected DI Salisbury in James Graham’s hit Nottinghamshire drama Sherwood, although he isn’t appearing in the forthcoming second series.

Yet in recent years he has also excelled at playing men who, deep into middle age, are struggling: Salisbury may have been a world-weary DI, but Glenister also exposed the bitter wounds of his recent divorce. “I think men, when they reach a certain age, can feel they are being let down by the system. Salisbury certainly felt that,” he explains. “And it’s dreadful to be told your career is over when you’ve dedicated your life to it.”

“Tony feels washed-up and spat out. Each of the men in The Night Caller are damaged and vulnerable,” he adds. “What’s more, they are all in their 60s. That’s not something you see often on TV.”

Glenister’s rumpled everyman face lends itself to these parts: in The Night Caller, the camera spends an awful lot of time silently watching Tony as he drives – a bold move, says Glenister, in a medium increasingly keen to give viewers “an instant hit”. But he also knows what it feels like to be under extreme pressure. In 2017, during a preview performance for David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross in the West End, which also starred Christian Slater, he blacked out on stage. He recovered, got through press night (the show received excellent reviews), and then it happened again.

“This cloud descended. I tried to shake it off but it became increasingly difficult,” he says. “What struck me was how quickly it manifested. But at the same time I was going through this tribunal with Equity and the taxman. I had an awful lot on my mind.”

Glenister and his younger brother Philip, the actor best known for the BBC drama series Life on Mars, had found themselves trapped by retrospective changes made to National Insurance. Around 60, mainly BBC, actors who had assumed they classified as freelancers, had been informed by HMRC – after a four-year decision- making process – that they were in fact employees and owed thousands of pounds in back-dated tax.

In the case of Glenister, who appealed, and lost, the total sum was £150,000. “Thanks to Hustle, I got called ‘TV’s conman’ and ‘the tax dodger’ in the press. It got to me a bit. Because I hadn’t done anything wrong.” He had to remortgage the house he shares with his second wife, radio producer Celia de Wolff, to pay it. “To be honest I think we will have to sell it in a couple of years. Because I simply can’t afford to pay it off. I don’t mind if HMRC wants to change the law – but just tell people when you do it and don’t make it retrospective. It’s not fair.”

Happily, the blackouts didn’t derail his stage confidence: he got through the rest of the run. A brief flirtation with being a police officer notwithstanding, he has always known he wanted to be an actor. He was a shy child “with protruding teeth”, but drama brought him out of himself. “You can see why teachers are leaving the profession in their droves,” he says. “These days they are told what they can and can’t teach. And increasingly they can’t teach the arts. Which is madness.

Because regardless of whether children want to be an actor or a musician, the arts really help those who lack confidence.”

Acting runs in the Glenister DNA: his son Tom, with Celia (he also has a daughter from his previous marriage to Amanda Redman), played Salisbury’s younger self in Sherwood, while his father, John Glenister, is a former TV director, helming shows such as Rumpole of the Bailey and Dennis Potter’s Casanova. Young Robert and Philip would often spend their Saturdays at Television Centre. “There would be Colditz filming in one studio, Grandstand in another. It was like a giant playground.”

Glenister joined the National Youth Theatre as a teenager and went straight into TV work from there – did he ever feel his lack of drama school training? (Philip, who fell in love with acting in his early 20s, went to Central School of Speech and Drama.) “Yes. When I started to work in the theatre I became a bit unstuck,” he says. “I played Bazarov in Fathers and Sons at the National in 1987 and I wasn’t very good. I was winging it, basically. If I’d been to drama school I might have had a technique. Instead, I had to learn on the job.”

He admits that he would love to do more comedy, although he laments the decline of the live audience studio-based sitcom. “It costs a fortune to make. It’s like the game shows now – you no longer have live studio audiences because of the cost. It’s a real pity.”

Yet he continues to work: next month he’s off to Brighton to star in Sky Atlantic’s adaptation of the Nick Cave novel The Death of Bunny Munro, starring Matt Smith. He gives another chuckle. “The sort of actor I am, there is less competition,” he says. “Whereas if you are a tall handsome leading man, you are up against it. You simply don’t get so many jobs as a result.”

The Night Caller begins on Channel 5 on Sunday, July 7

2024-06-29T13:18:09Z dg43tfdfdgfd