THE FRIDAY AFTERNOON CLUB BY GRIFFIN DUNNE REVIEW – A HOLLYWOOD INSIDER WITH AN OUTSIDER’S EYE

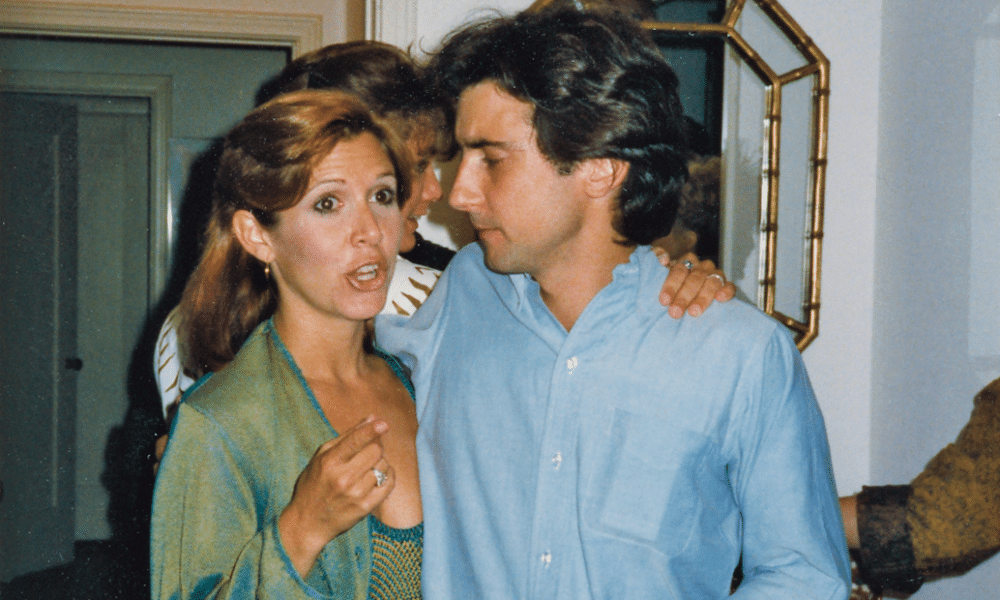

For those less well-versed than me in the world of high 1980s Hollywood and its various satellites – or do I mean parasites? – it may be useful if I begin this review with a brief biography of the book’s author. Griffin Dunne: does the name ring any bells? It probably should, but let me elaborate anyway. Dunne is an actor (An American Werewolf in London) and a producer (Baby It’s You, After Hours). His father was Dominick Dunne, Vanity Fair’s star reporter in its pomp under Tina Brown, and his mother was Ellen “Lenny” Griffin, an heiress who was close to Natalie Wood. His uncle was John Gregory Dunne, another writer, who in turn was the husband of Joan Didion, the celebrated author of such nonfiction classics as The White Album and Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Elizabeth Montgomery from Bewitched was his babysitter. Truman Capote was a guest at his parents’ 10th wedding anniversary party. Carrie Fisher was his best friend.

But The Friday Afternoon Club, a memoir of Dunne’s life until, at 34, he has his first (and only) child, isn’t just another celebrity Rolodex. For one thing, there’s the way it’s written, so honest and funny and smart. Dunne handles everything – and everyone – with the scabrous aplomb of the outsider, something that he most definitely is not; his tone is a little bit Holden Caulfield (The Catcher in the Rye), and a little bit Benjamin Braddock (The Graduate), with a few icy chips thrown in – picture me now, jiggling a delicious aperitif in my hand – that might have come straight from one of the notebooks of his late aunt Joan (more on these frozen shards later). What I mean is that on the page, he’s both adorable and exasperating: if he’s Tigger-ish and easily bored, he’s also nobody’s fool. Always the first to laugh at himself, he is utterly lacking in self-pity.

What makes all this the more remarkable is the fact that at the heart of his book lies near-unimaginable pain and suffering. With huge daring, Dunne gives the reader a detailed, highly intimate account of the circumstances surrounding the death in 1982 of his 22-year-old actor sister, Dominique, who was strangled by her abusive ex-boyfriend, John Sweeney, without ever allowing it to derail the picaresque adventures he describes elsewhere. It should be as clunky as hell, this combination, but somehow it never is, perhaps because Dunne has known ever since he was a young man (he’s 69 now) that even when people are in darkness, they are still apt to make jokes, and sometimes to cry with laughter – and he won’t shy away from it. Doubtless the reader does exist who will find it strange and bewildering that as Sweeney’s trial proceeds, Dunne spends the hours when he’s not in the courtroom doggedly making a movie and almost cheerfully working his way through a sheet of LSD prepared especially for him by Timothy Leary (a present from an ever-thoughtful Fisher). But most will find it both bracing and incredibly human. I know that I did. What a guy, I kept thinking, as I wolfed his book down. And: what would his publicist think if I asked to take him out for lunch the next time he’s in London?

Fame, as he makes plain, is corrosive: it changes friendships; it feeds narcissism

Dunne seems to like lunch, in the same way that he likes almost everything: if character is destiny, his nature is generous and grateful. But this doesn’t mean that he isn’t also clear-eyed. His account of Dominick Dunne’s fall from grace in Hollywood, where he worked first as a producer, is straightforward to the point of briskness, and all the more loving for it (this descent, which saw him selling all his possessions and living in a cabin in Oregon, was born of alcoholism and, perhaps, of his secret gay life); nor does he hide how uncomfortable it makes him that his father’s second act, as the kind of journalist who was never off the TV talkshows, came about only because he covered Sweeney’s trial for Vanity Fair. Fame, as he makes plain, is corrosive: it changes friendships; it feeds narcissism. His pen portraits of everyone from Sean Connery (who once saved him from drowning) to Tennessee Williams (who groped him at a dinner party) are as deft on this score as his accounts of his own disasters; of the public scrapes and hilariously bad decisions that trail him as a cloud of dust does Pig-Pen in Peanuts (yes, he really did star in a film about a man whose penis chats to him).

He doesn’t forgive his sister’s killer – to the horror of the Dunnes, Sweeney was convicted only of voluntary manslaughter, for which he served just three and a half years in prison – but his hate burns itself out in the end; that, or he somehow lets go of it. Elsewhere, though, forgiveness becomes a theme. I hadn’t realised that Dominick Dunne was on such bad terms with his brother, an enmity that only grew when John elected to take Joan and their daughter, Quintana, to Paris for the duration of Sweeney’s trial on the grounds that they didn’t want Quintana called as a witness – a decision that puts a new light on them entirely, I think (especially Joan, who was so praised in the last years of her life for her stoicism after the deaths of both John and Quintana, she began to take on the air of a medieval saint). There’s something horribly gelid here – later, John makes the situation worse by writing in the New Yorker of his unaccountable disdain for those who attend the trials of those accused of murdering “their loved ones” – and yet, somehow, Dunne finds a way past his, never quite falling out with his aunt and uncle himself.

Perhaps, it occurs to me now, this is why his 2017 documentary, Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold, is so good: even as it honours its subject, a chill rises from it, as if from a lake in wintertime. Certainly, it’s what makes The Friday Afternoon Club (named after the gatherings Dominique held at her pool house in LA) so much more than the book you feared it might be. He doesn’t spell anything out, save for his own ridiculousness. But he doesn’t need to. The reader draws her own conclusions: feasting on the glamour, laughing at the absurdity, shivering as the icebergs float silently into view.

The Friday Afternoon Club: A Family Memoir by Griffin Dunne is published by Grove Press (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply